By Steve Paul

John Kenneth Galbraith, the great patriarch of liberal economics, had something to say, and he was going to say it right here, right now.

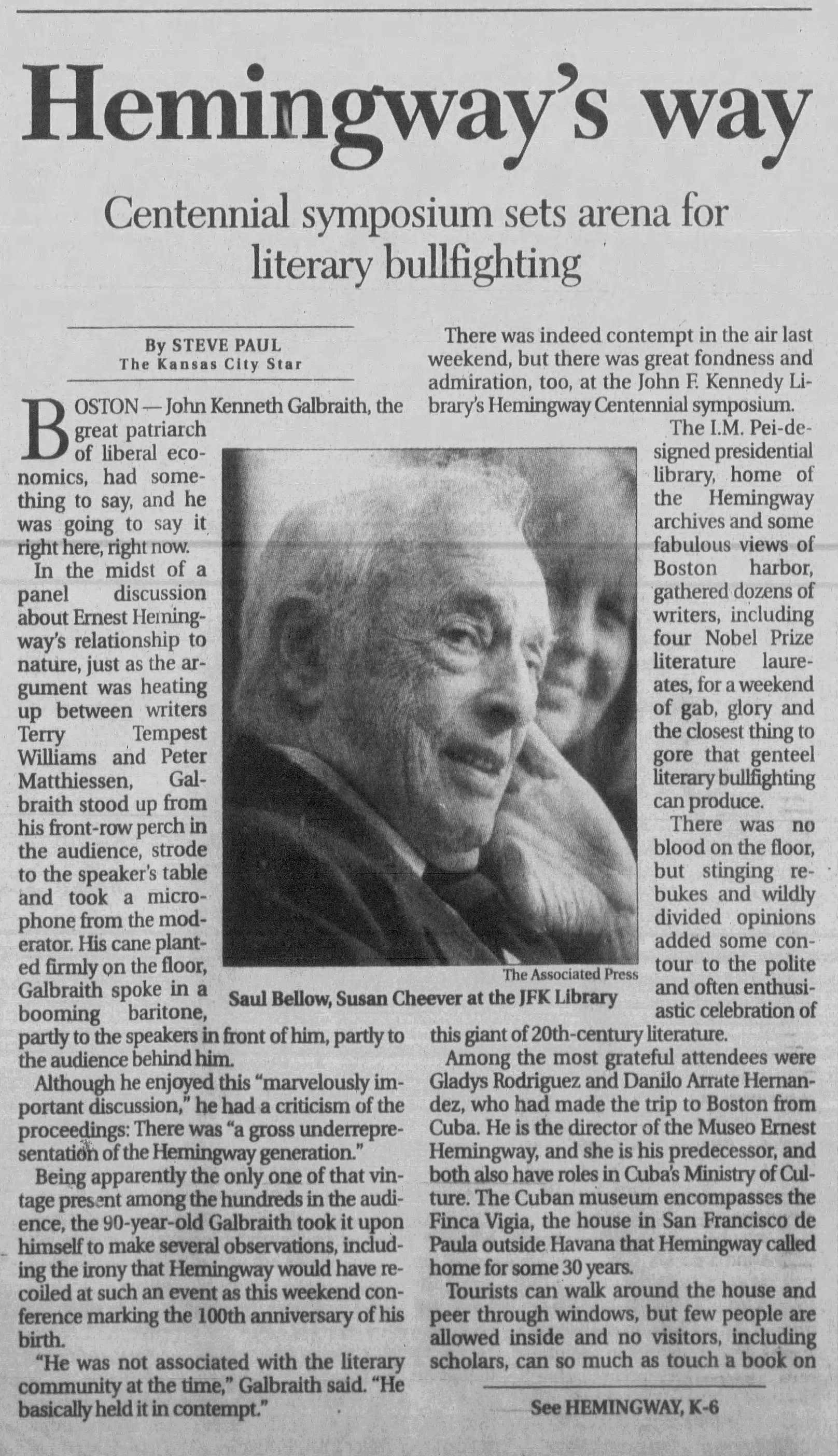

In the midst of a panel discussion about Ernest Hemingway's relationship to nature, just as the argument was heating up between writers Terry Tempest Williams and Peter Matthiessen, Galbraith stood up from his front-row perch in the audience, strode to the speaker’s table and took a microphone from the moderator. His cane planted firmly on the floor, Galbraith spoke in a booming baritone, partly to the speakers in front of him, partly to the audience behind him.

Although he enjoyed this “marvelously important discussion,” he had a criticism of the proceedings: There was “a gross under-representation of the Hemingway generation.”

Being apparently the only one of that vintage present among the hundreds in the audience, the 90-year-old Galbraith took it upon himself to make several observations, including the irony that Hemingway would have recoiled at such an event as this weekend conference marking the 100th anniversary of his birth.

“He was not associated with the literary community at the time,” Galbraith said. “He basically held it in contempt.”

There was indeed contempt in the air last weekend, but there was great fondness and admiration, too, at the John F. Kennedy Library's Hemingway Centennial symposium.

The I.M. Pei-designed presidential library, home of the Hemingway archives and some fabulous views of Boston harbor, gathered dozens of writers, including four Nobel Prize literature laureates, for a weekend of gab, glory and the closest thing to gore that genteel literary bullfighting can produce.

There was no blood on the floor, but stinging rebukes and wildly divided opinions added some contour to the polite and often enthusiastic celebration of this giant of 20th-century literature.

Among the most grateful attendees were Gladys Rodriguez and Danilo Arrate Hernandez, who had made the trip to Boston from Cuba. He is the director of the Museo Ernest Hemingway, and she is his predecessor, and both also have roles in Cuba's Ministry of Culture. The Cuban museum encompasses the Finca Vigia, the house in San Francisco de Paula outside Havana that Hemingway called home for some 20 years. Tourists can walk around the house and peer through windows, but few people are allowed inside and no visitors, including scholars, can so much as touch a book on the shelf in what was Hemingway's voluminous personal library.

The Cubans toured the Hemingway Collection at the JFK Library, an archive they could envy if only for its air conditioning. Arrate explained that his most important role is to preserve the thousands of books, manuscripts, photographs and other objects that remain at the Finca Vigia in a humid country strapped for cash and official friends outside its borders.

Stephen Plotkin, the curator of the JFK's Hemingway collection, referred to Rodriguez and Arrate as his personal heroes for the work they had done amid extremely trying circumstances.

“The Cuban people love Hemingway,” Arrate said in an after-hours conversation. “In Cuba, it’s as necessary to read Hemingway as it is Pushkin and Tolstoy.” Mr. Guey—pronounced Gway, which is a fond Cubanism for Hemingway, Arrate said— “is an integral part of Cuba's culture.”

Hemingway, of course, set one of his most popular books in Cuba, The Old Man and the Sea. And he has been an integral force in American literature ever since he arrived in Paris in the early 1920s and began publishing short stories and novels that demanded to be noticed as new and as modern and as revolutionary as anything being written.

He holds the distinction, too, as one speaker pointed out, of being the only American writer to have published a new book in every decade of the century since the 1920s.

Underlying some of the weekend’s discussion was the knowledge that readers soon will have a chance to see one last big work from Hemingway's hand. True at First Light — a fictional memoir, it’s called — has been edited by Hemingway's son Patrick and will appear later this spring, closer to the July 21 centennial date.

The book is set in Africa during a Hemingway safari in 1953-54. (One story line involves Mary Hemingway’s desire to shoot a big elusive lion, the result of which now lies on the floor of the JFK's cozy Hemingway Room.)

True at First Light is bound to raise anew significant questions about Hemingway's competence in writing about Africa. Two of his best-known Africa-related short stories, “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” are certainly brilliant, said Nadine Gordimer, the South African Nobel laureate, but they are not about Africa. Instead they “are typical of the attitude that Africa was a place to come and play.” Gordimer set the good-news, bad-news tone for the conference in her keynote address. She said Hemingway “never had both feet down in Africa,” largely because he never tried to understand or to write about its people except in the most patronizing and superficial way. But she also acknowledged much of his work belongs among the “essential literature of the 20th century” and urged her audience to “leave his life alone,” meaning the problematic legend that he created for himself, and return instead to his books.

Revisionism and fisticuffs

The several hundred symposium attendees also heard from writers as diverse as Japan's Kenzaburo Oe; the West Indian poet Derek Walcott; and Americans such as fiction writers Saul Bellow, Robert Stone, Tobias Woolf, Francine Prose, E. Annie Proulx and Leslie Epstein, the critic Henry Louis Gates Jr. and the editor and raconteur George Plimpton.

For Oe, discovering Hemingway's earliest short stories was as important as discovering Mark Twain, and he made a brilliant comparison between Hemingway's young character Nick Adams and Twain’s Huck Finn. Walcott offered a singular analysis of some of Hemingway's prose in his bullfighting book, Death in the Afternoon; the rhythmic structure and musicality of some of his sentences were the equal, Walcott said, of anything in Dante and Shakespeare.

Justin Kaplan, biographer of Mark Twain, Walt Whitman and others, expressed a common lament that “Hemingway has been commodified, Elvisized.” Taking issue, for instance, with a volume of Papa-related recipes called The Hemingway Cookbook, Kaplan said, “This is like casting Emily Dickinson as the cookie baker of Amherst.”

Many of the scholars in attendance, the kinds of people who make careers out of studying everything about Hemingway down to the last missing comma, were appalled, but said so only privately, by the lack of understanding or preparation they heard in various panel discussions.

The panels were made up largely of well-known writers rather than academics. The memoirist Susan Cheever, for instance, showed an astonishing level of breathless, presumptuous naivete, which was occasioned by her reading of Hemingway's A Moveable Feast and other examples of his nonfiction in just the previous week. Really?

Another of those blood-boiling moments occurred during a panel on the role of biographers. A.E. Hotchner, who palled around with Hemingway for a time in the 1950s and later wrote a hero-worshiping memoir, tried to counter what he thought was misinformation about A Moveable Feast. Hemingway's popular memoir of Paris in the 1920s was published in 1964, three years after his suicide, becoming the first of what will be now five major books published since the writer's death.

Hotchner said A Moveable Feast was not cobbled together after Hemingway died, as some critics and researchers have contended; Hemingway wrote it in the 1920s, and it appeared as he intended. Hotchner himself was on the scene, he said, at the Ritz Hotel in Paris on the day in 1952 when Hemingway was given a Louis Vuitton trunk of his that had been in storage for many years. Among other things, the trunk contained manuscripts of the personality sketches of Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald and others that made up A Moveable Feast.

All the while Hotchner was telling this tale, biographer Michael Reynolds, two seats away at the panelists’ table, shook his head in disbelief and looked ready to pounce. Reynolds has virtually lived with Hemingway for some 25 years to produce a five-volume biography, the last entry of which will appear in July. He soon gently chided Hotchner by saying that all the evidence, including letters between Hemingway and his last wife, Mary, indicates that “a good deal of that book was written near the end of his life.”

Throughout most of the presentations, Hemingway family members, including sons Patrick and Jack, patiently listened and graciously received the verbal fisticuffs. Carol Gardner, Hemingway's youngest sister, had heard few surprises, she said on the conference's second day.

When asked about her fondest memories of her brother—he was 12 years her elder—her eyes lit up with the memory of how she would stand guard for the teen-aged Ernie while he boxed with his friends in their mother's music room.

“I not only let him know if Mother was coming in,” she said, “but I also would hold a bucket of water in case he got a bloody nose.''

And that, she said, would happen every time.