The photographer Julie Blackmon has rocketed to commercial success from her modest and raucously domestic base in Springfield, Missouri. Last night (Oct. 7, 2022), she opened a new exhibit, “Metaverse,” at Haw Contemporary in Kansas City. It’s a stunning display of her recent work, and there’s also a survey of her earlier work in two galleries upstairs. I chatted with Julie for a few minutes during the crowded affair. We had connected, alas, only by phone in late 2008 for a magazine piece I wrote about her. At the time, she had begun to evolve beyond black and white photos into a glorious and surreal world of color, mostly involving children—hers and those of her siblings and neighbors—in theatrical and often eerie compositions. She was just beginning to get noticed. She told me how grateful she was for this story, which was one of the first in-depth pieces that took her and her art seriously. Friends gave her laminated copies of the multi-page article. The story is largely lost and virtually unobtainable in KC Star archives; I was able to snare black-and-white copies of the magazine pages. But I also miraculously found a printed-out draft of the article, which I’ve used for the text here, with a few silent and immaterial edits. (I’ll overlook a couple of my clunkier sentences.) The story appeared Feb. 1, 2009, in the Kansas City Star Magazine, under the headline “Controlled Chaos” and accompanied by numerous photos from her work at the time..

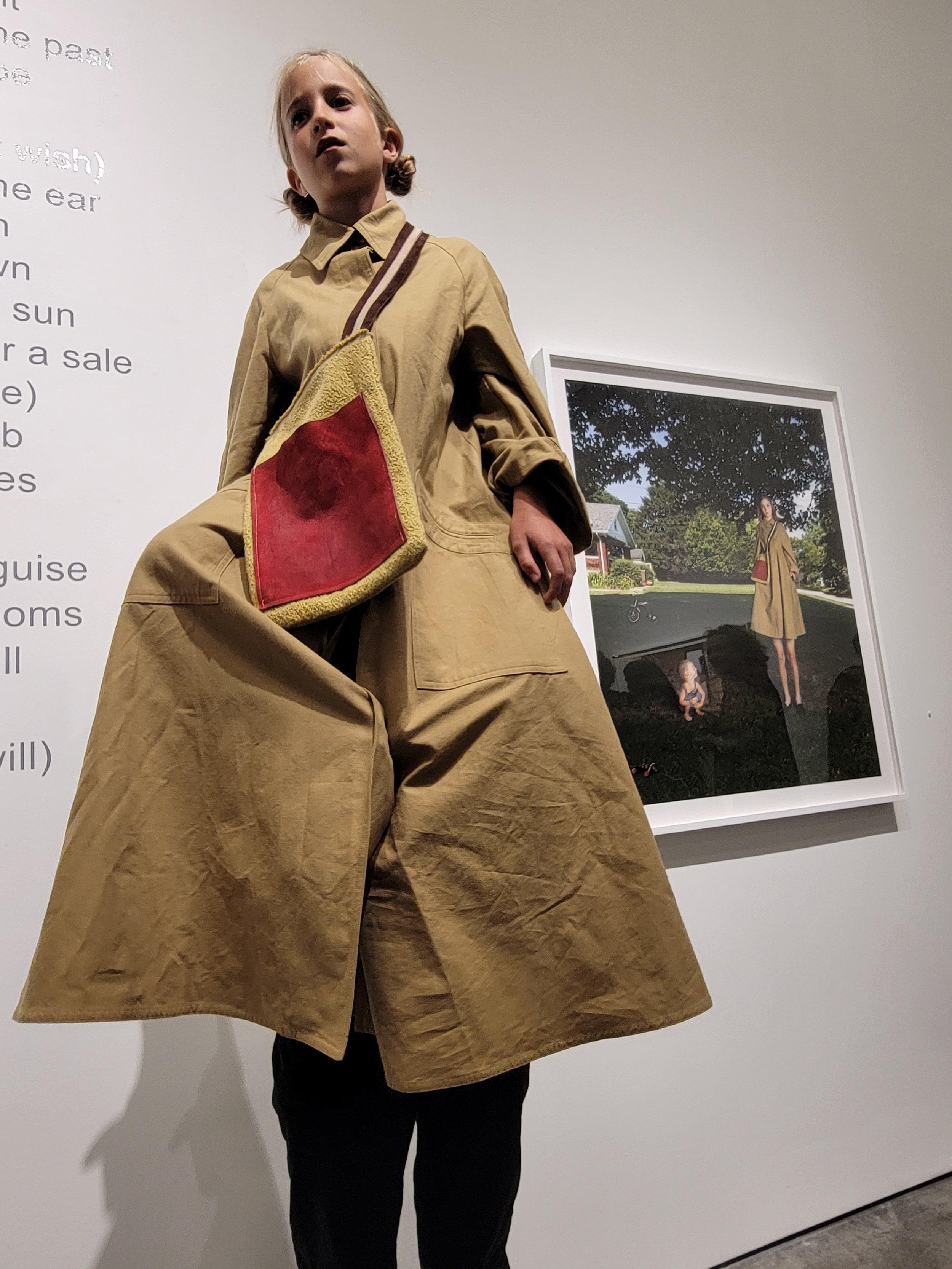

In the gallery above are my photos from the Haw opening. The event was populated with as many as 40 of Julie’s relatives. She said it was a gathering that may never happen again. I didn’t catch the name of the girl who re-enacted her physical enlargement in “Tall Girl.” But It definitely was a moment. I’m also including Julie’s two pictures in tribute to George Caleb Bingham, “Flatboat” and “Paddle Boat.” They are extraordinary and quite compelling. And they may well become a signature pair of images that speak to Julie’s deep engagement with American history, culture, and emotional conflict.

By STEVE PAUL

If the history of photography is any guide, children and cameras were made for each other. As subjects of human innocence—when they’re not subjects of mischief-making—children have provided photographers and viewers endless fascination. We learn about ourselves by what we see in them.

For Julie Blackmon, a Springfield, Mo., photographer who’s gaining wider art-world attention, the lives of children became not only a natural, recurring theme, but essential characters in her arrest, often wacky images of family life.

It’s easy to understand why. Let’s see: She grew up in a family as the oldest of nine children. Now, at 42, she had three children of her own. Most of her siblings live in the same Springfield neighborhood, and they all have children, too. Then add in the cousins and their children.

“It’s like some kind of Branch Davidian cult around here,” Black said by phone. “We’re not super religious. But I’m Catholic, and I ended up just having 75 relatives in the same neighborhood.

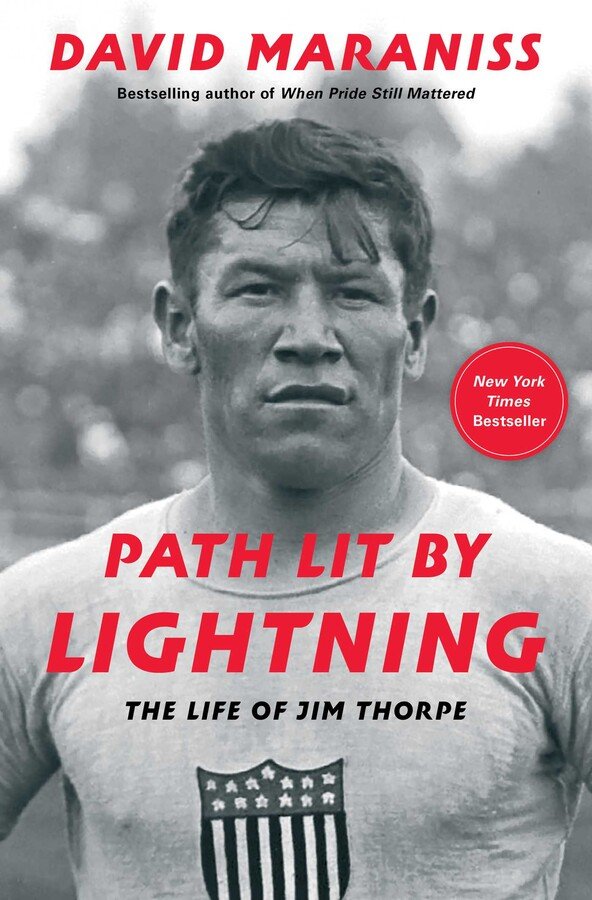

Three dozen of her extended-family photographs are collected in her recent book, Domestic Vacations, published by Radius Books, a small, art-book specialist in Santa Fe, N.M.

From the cover image of the barefoot, red-caped, apparent troublemaker in “Time Out” to her many antic arrangements of space, color, cavorting kids and carefully orchestrated details, Blackmon’s photographic project clearly is the work of a keen-eyed artist and cultural critic but also a sometimes harried parent.

“I think this body of work is about me sorting it out,” she said—sorting out the stress of high-pressure parenthood and balancing the memories of her mother’s scream-filled household with the challenges of her own.

Just the other day, with a writer on the other end of the phone, screams erupted in the background. It seems her 9-year-old son, Owen, was tormenting one of his teenage sisters over the matter of a smashed Wii.

It was a teacher work day, and the kids had a day off from school.

“There’re way too many of those,” Blackmon said.

***

Like Sally Mann, Ralph Eugene Meatyard and a legion of other photographers before her, Blackmon, with her richly composed narratives, explores childhood imagery in the borderland of surrealism.

Take “Birds at Home.” Five children appear on, around and under a dining table, each seemingly lost in his or her own moment. The infant on the table pets a cat. A girl stands on a chair, the hem of her dress in her mouth. Another leans on her elbows, hand holding chin, like a princess in then making. A boy on the floor looks at a toy dinosaur. Another kneels on a chair, his face buried in a picture book from which the photograph takes its title, Birds at Home.

Despite the daylight a chandelier burns bright. There’s a mixing bowl on the table, an errant beater on the floor and whoever left the Starbucks cup at table’s edge is nowhere in sight.

Controlled chaos for sure.

But wait, there’s more: An egg carton lay open and six shells broken neatly in half litter the table and floor, lending the scene a Gothic twist. Have these five children been hatched in some nightmare fantasy? Dows the sixth broken egg belong to the parakeet perched at photo’s edge, or to the black-and-white cat, or the red-headed doll sprawled in the lower corner like some fallen putto?

This is typical Blackmon. Her pictures are multi-layered scenes, compressing time, action and psychological states of mind. It’s almost as if a short film had been collapsed into a single frame. There’s always something in the deep space or a tiny detail in a corner that she wants you to notice—an errant piece of gum, a fallen “tippee cup.” Children appear upside down, on the verge of danger and every which way, especially loose.

“There’s a playfulness and a huymor to her work that is really refreshing, said April Watson, assistant curatorof photography at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, which acquired two of Blackmon’s images not long ago, including “Birds at Home.”

“She shows the activity of childhood play is not just sugar and spice. There’s decapitation of dolls, that kind of thing. There’s a lot of violent acts, I think, that anybody who has young children knows it’s a very much part of play.”

Some of Blackmon’s scenes consciously reference the paintings of Jan Steen, a 17th-century Dutchman so well known for his raucous pictures of everyday life that they spawned a cliché—“a Jan Steen household.” :ike Steen’s canvases, Blackmon’s frames are filled with good-humored satire.

And in their topsy-turvy domestic worlds, both speak to contemporary parenthood, Watson said.

“You can never quite keep things together,” she said. “And the kids sometimes ssem to be ruling the roost. That’s one of the things I definitely love about her work.”

Blackmon’s pictures converse with contemporary culture, consumerism and art history in general. Sephora bags and iPods appear not just as name-brand props, but as comments on social priorities. And it’s not hard to make the visual connection, in “Candy,” between the girl in a blue velvet dress and the framed reproduction behind her of Thomas Gainsborough’s “Blue Boy,” an iconic childhood painting and once one of the best-known piece of Western art.

***

After a decade of being a housewife and mother, Blackmon renewed a long interst in photography six years ago by taking classes at Missouri State University, where her husband, fiction writer W.D. Blackmon, heads the English department. Years earlier, she’d been a photography major, but never finished her degree.

“I wanted to do something besides watch ‘Oprah’ every afternoon,” she said. “So I thought I’d take pictures of kids. The idea was to take better photographs to hang on the wall.”

She started working in black and white, convenient given that a previuous owner had equipped the Blackmons’ century-old house with a basement darkroom. Her sisters encouraged her to put the darkroom back in action.

And the more pictures she made, the more serious she got, and as she began to get feedback from awards judges, curators and her sisters, she knew she was onto something. She turned to color, and her photographs became increasingly complex scenes.

As an art form photography operates under a big tent. Some believe in a kind of pure photographic truth, where a documentary artists, composing a frame and snapping the shutter at a proverbial “decisive moment,” captures light and life in a way that makes mere reality more meaningful.

Blackmon began there, wielding her Hasselblad to take a documentary approach towards children at play.

Nowadays she tends to belong to the camp where artists make their truths with far more obvious interventions: staging events, constructing narratives, manipulating images with all the tools PhotoShop has to offer.

But her evolution involved more than just technology.

“You could see the path she was on,” said Kathy Aron Dowell, who showed Blackmon’s work at the now-defunct Society for Contemporary Photography gallery. “She was doping black and white work of her children. It was beautiful, but it didn’t have the personal vision that I see in her work now.”

Experiment and manipulation in photography dates back to some of the earliest daguerreotypes of the 19th century. And, said Watson, the debate over purity in photography heated up again in the 1970s and ‘80s as photographers such as Sandy Skoglund, Cindy Sherman and C=Gregory Crewdson adopted what was termed the “directorial mode,” staging scenes and inventing installations to be captured on film.

“They were creatimg something to be photographed as opposed to ging out intothe world to make photographs of what one encounters,” Watson said.

Digital technology has expanded the available tools exponentially, making it that much easier for photographers and “new-media” artists to blur the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction.

Blackmon compares her way of working to writing, painting and film-making. Just as her husband borrows and exaggerates real details of life to write stories, she arranges, compiles and composes pieces of real life with fanstastical inventions and combinations of multiple images.

“Sometimes I can get an image all in one shot,” she said. “Sometimes it’s 17 shots. In the end, it doesn’t matter. It’s just a different way of working.”

But she also believes that, despite working two weeksor more to plan a picture, her best work results from those spontaneous convergences of light and action—thank you, dear child—that remain the essence of photography.

“There’s just a degree of that you can never totally create,” she said. “Some of that is completely out of your hands.

Lately Blackmon has been making prints—huge ones, as wide as 54 inches—for new exhibits, including one that opened in Januaty at the Fahey Klein Gallery in Los Angeles. Shows will follow this year in San Francisco and Boulder, Colo. The Nelson-Atkins is planning an exhibit for later this year of contemporary photography and children and Blackmon “almost certainly” will be in it, Watson said.

What with the holidays and printing, Blackmon said, “I haven’t madea new image since November.”

And then there’s that thing called real life.

Another interruption: Owen is standing nearby with his coat on. A charger for a Nintendo is lost and they’d have to use the one that works in the car. But mom’s on the phone.

“Here I go, out to the car,” she said. “Trudging through the snow.”